res_plot

|Development Repository| |Report PDF| |Merge Request|

I just finished finals and I'm about to get into gear to start my project with the Blue Brain. This week I'm trying to figure out how to get their latest Neuromapp program forked into my gsoc directory, and ensure that I haven't forgotten all of the C++ I ever learned.

Had a fun week watching other people freaking out with the endings of finals, and the graduation ceremonies happening all over town.

On a project related note, I also managed for setup a fork to Neuromapp, and an upstream connection to the original repo. In the process of building the neuromapp I realized how little I know about the use of CMake, so there's been a ton of reading involved so far. My manager also sent me his container that I will be experimenting with compression strategies on. Part of the day went to making sure that I could compile that, and do a little looking around inside the code.

I had a fun little moment yesterday when I tried to push a commit that had included my build directory. Both my manager, and git immediately jumped on me haha! Ok, lesson learned. This morning I fixed that up and made a few additions so now the start of my compression mini-app for neuromapp has begun.

I'm currently a little bit stuck on how to include the suite of boost tests that my mentor has passed on to me, but he says that stuff can wait.

Next week I'll be working on getting some tests for the user command line interface up and running, and trying to get more and more familiar with the basic state of the project as it exists outside of my contributions.

Stay posted!

This week I got to move a little further along with setting a foundation for the compression work to come. I double checked that neuromapp could still compile with last weeks changes. Additionally, I wrote a custom cmake compile script that would exclude the mini-apps not needed to test changes made to the compression app. With this I can modify compression app code and compile to check without having to wait for the whole program to rebuild.

I then tried to run some of my manager's tests for the block structure. I had to modify Cmakelists in various subdirectories to get neuromapp to acknowledge the tests, but currently they are giving me the green light. It's taking a little bit of time to parse the boost::mpl templating that Tim is using for the unit_testing but I think our most recent conversation has cleared up most of my lingering questions.

Later in the week I started coding the boost::program_options functions that are necessary to use the block through the neuromapp command line interface. It took a little bit of time to read up on how to do this, but the end result is very nice. I then attached the zlib compression library functionality, and created a demo option for the neuromapp compression tool. This demo uses a string buffer as a compression object and prints out its size in memory before and after compression. This is in some sense a metaphorical hello world compression exercise.

Following this progress my mentor suggested that I make sure I feel completely comfortable with the code supporting our block memory object, and so I spent a day revisiting the code. Upon reading my update email for the day Tim said that at some point he needed a prefect function. This I took to mean a "perfect" function which I'm convinced will never exist no matter how clever the programmer is. Needless to say I was a little freaked out by how high the bar was getting set, so I wrote back asking if he was joking. He corrected my misunderstanding by explaining that a "prefetch" function is what he meant. If you're wondering this is essentially a function that helps to make sure that data needed for computation is within reach when its needed; if you have a sense for it, this can provide significant optimizations for your program. After learning about this, I went about creating a number of examples to cemente my understanding.

That about wraps it up for this week!

Until next time

This week gave me a good impression of what the rest of the summer might look like as far as the summer of code is concerned. In summary I worked on compression of non-trivial objects, setting up the program environment for boost::hana, combating Cmake strangeness for header paths, and learning some policy based code structure.

The compression part is still giving me a little bit of grief. So last week I brought into the neuromapp program a small practice function where I compressed a string that said "hello compression" and uncompressed it to see the result. All that went well, so I moved on to trying to compress an empty block, and this didn't go so smoothly. After a conversation with Tim, I learned that there are higher level compress/uncompress utility functions from zlib that I could be using. With this info I happily attempted that implementation, but currently the result of uncompress is a mostly empty block with its first element containing a large negative number, pretty wierd right?

Instead of spending the entire week on that issue, I move on to look at how we can bring in the hana boost meta-programming tool. This was also less straightforward than I had hoped. On boost's page they explain that if you hope to use hana with Cmake you need to simply setup hana as an externalproject for use. I'm not very well versed in Cmake so when the instructions ended there I was dissapointed. To further complicate this issue hana needs the most recent boost package, and g++/gcc compilers. I realized after the fact that my approach to this twist could have made my life harder, but I eventually figured out how to include the correct path so that neuromapp could build with access to the boost/hana.hpp. This whole process has left me feeling slightly more adept with CMake.

This week I was also provided with some sample data to fill out the blocks so I spent some time diving back into IO. I made a couple of generic functionss that could read the data into a block with user specified dimensions, and then had to make a specialized version to create a tiny 1row block holding the header row for the data. This wasn't the easiest thing I ever did, but it currently works for files that are csv's containing float data. I'd like to figure out next week what can be done to make that more flexible, but the compression issues are likely to be my priority.

With all this said, I think I'm getting pretty comfortable with the code that Tim has given me now that I'm having to extend it in various ways. I hope that I can resolve these issues by next week so I can begin my implementation on a compression policy to attach to the block class.

See ya!

Memorial day was last monday, and for some reason this day manages to be a struggle for me every year: 2 years ago I botched some travel plans and had to camp out in Riverside California; the next year I almost lost my bike boarding an amtrak to go home; this year I lost my wallet and did a few laps around town retracing my steps. Once I found it, I decided to just hide at a coffee shop hoping nothing else would go wrong.

Outside of coding I've been attempting to work through a scary looking trello tab. I'm presently raising funds for my trip to the Neuroinformatics 2017 congress in Kuala-Lumpur, and so had meetings with a few people in my department about travel grants. I also had a meeting with my spring semester Linear Algebra professor to discuss Singular Value Decomposition strategies that might apply to my compression project. Yesterday I attended my first scientific programming bootcamp hosted by the CS department which is helping to patch up holes in my existing c++ knowledge. All fun and helpful stuff to be sure!

Since this week is the official beginning to the summer of code it make sense that there was plenty to do. I found out that I had misunderstood what the block reading process entailed, and spent time on Monday and Tuesday getting the >> and << operator setup with the block object. Block input and output operations are now accomplished by stream redirection which most c++ programmers would expect. Once this was set Tim suggested that I create some boost unit tests. Boost is pretty new to me so this came with a bit of an upfront learning curve. I'm still working out the details of why certain cases fail the tests I wrote, but otherwise we are getting supportive results. Most importantly, I put together a zlib un/compression policy following some of Tim's designs that should allow for compression specific options to be set at the time of block declaration. I'll talk more about why we are approaching block compression in this way when I have a better understanding of policy based design.

Later today I'll be trying out my very first block compressions, and addressing the strangeness that springs up there. Next week I imagine I'll be setting up unit tests for the compression policy, and starting to read about the uses of inflate and deflate functions that zlib provides to customize my compression to the block.

This week went by in a flash. I started out with the task of making some further changes to the method that reads data into our block. Last week I ended with a setup that allowed for checking block outputs against a hardcoded correct version, but it became pretty clear that this was only "correct" when we had a block of numeric type float. After this week's modifications we are almost at the point where we can convert an original file's contents into the form that would be correct if the read goes through regardless of the block numeric type.

A few days ago I also had a mini breakthrough: I compressed and uncompressed my first block, and the output passed the comparison to a copy made before compression. Currently this is using a method that Tim doesn't prefer, so I'll be looking into how I can accomplish this through an alternate route next week.

Next week I imagine that I'll be continuing to refine the tests, and creating a complete suite of compression tests.

I apologize for any typos, but I just had my eyes dilated at the Optometrist's office, and I'm working against certain visual distortions.

This week was the ending of one phase of my project and the beginning of the next. I have been working since my semester ended on setting up a framework for compression experiments using the neuromapp block datatype. Starting this week I finished my test writing, and confirmed that the block can have data read into it from a specific file, compressed, and uncompressed without permanent changes to the block. This means that now I'm poised to launch in the research phase of the project where I experiment with different libraries, and compression techniques to figure out what is the best implementation to carry into the last phase of the summer of code.

along the lines of these possible improvements I looked into sorting in the last couple days of the week. For 1 dimensional blocks, this was a trivial task that yielded a small gains in our compression factor. The next step that I've been trying to work out is how to leverage the STL sort algorithm for 2 dimensional blocks. It looks like I'll be making up a custom iterator class to apply the working 1 dimensional sort to each column of a block one at a time.

I then went back to the command line tool, and updated it to reflect the changes that have happened to the block since the third week. Back then I hadn't accomplished a working version of block compression, or sorting, so both got rolled into optional flags for a benchmark. This run outputs various stats about block compression for each file in a specified directory.

Next week I'll be working out the 2 dimensional sorting, and then trying to create another zlib compression option which allows users to specify the compression level they want applied to the block.

ciao!

Its almost funny just how simple sorting a 1 dimensional block is. We just say to the STL sort algorithm "here's the beginning of my block, and there's the end... have at it," and it does! Unfortunately the do what I say and do what I mean aspect gets a little muddied when the block is 2 dimensional. In order to tackle this issue in a way that means at the higher level we still only have to call STL sort for our purposes I set about creating a custom iterator for the block. Foolishly I jumped right in at the Random Access Iterator that is required for sort, without much of a clue about how to implement even the most basic custom iterator. After a day of dealing with compilation errors that left me without much of a sense of progress I shifted to a new branch to incrementally design this beast of an iterator. Going from input iterator to forward to bidirectional wasn't much of a problem, but there was still something of a jump in difficulty to enable random access to positions in the block through an iterator. On Thursday evening I hit the sweet spot of defining enough, but not too many, operators so that sort would zip down a specific column of our block, and leave behind whatever order was given as a predicate.

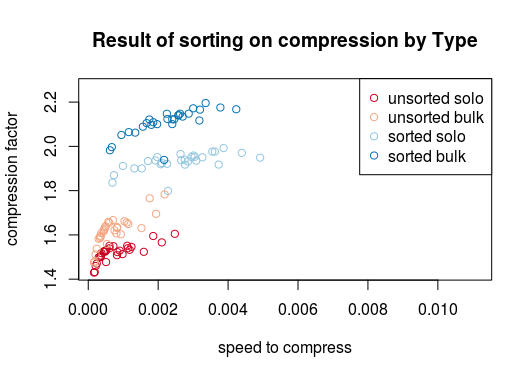

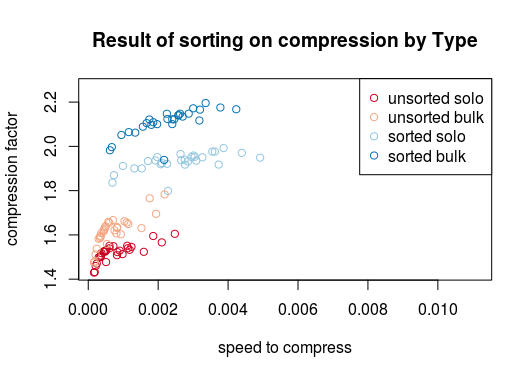

Very pleased with myself, I began the task of determining whether this improved our compression at all. Fortunately last week's benchmark improvements left me with a means to output all kinds of stats about runtime performance using a whole directory of files. Having cranked out results for sorted, and unsorted blocks alike I cleaned and briefly analysed the data. If I've been successful attaching this image, you will see that the sorted blocks lead to greater compression factors almost across the board.

res_plot

what a week! Next week I'll probably be playing around with the zlib utilities in a 2.0 fashion, and maybe event some incredibly low level shuffling of the memory making up our block's data. All in the name of greater levels of compression!

The last couple of weeks seem to be following a nice sequence of experiment, formalize, analyse. Two weeks ago I was fixing a mistake from the previous week in the way that the column sorting was being performed. Instead of sorting each column row by row from largest to smallest I was supposed to sort an entire block's collection of columns depending on the values within a specific row. Subtly different (perhaps not so subtle).

With a little bit of experimentation I found that another STL tool called "swap_ranges" was going to do exactly what I needed. To formalize this into an actual process I only had to figure out what the correct order of the specified row was. Then I could use that to guide where the swap ranges were applied to pairs of iterators (top and bottom of column).

In analysing blocks that were sorted this way before compression it was clear we were able to get compression factors around 2 times greater than when performed on the original blocks.

sorting benefits

This week was much the same, but with an arguably easier transformation performed to the block. Before going any further its worth pointing out that floating point numbers have several different representations: you can have the IEEE745 representation, or you can convert to a triple of binary sets with parts known as the mantissa, the exponent, and the sign. The mantissa is essentially the decimal representation in base 2 once the number has been normalized (decimal place shifted). The exponent is the factor of 2 to the power of the number of places that the decimal was shifted in the previous step. the sign is a 0 or 1 bit representation of whether the original number was positive or negative.

The whole transformation boils down to copying each value from an existing block of floats into a new block where like parts of the triple representation are stored together:sign sign sign sign, ... ,exp exp exp exp, ... , mantissa mantissa mantissa mantissa...

When compressions were run on this instead of the original block we got compressions on the scale of 3x better than those of the original block.

split benefits

Now that we have a couple of varieties of compressions methods it's time to check on whether we get performance improvements using compression and uncompression as part of the kernel in the tsodyks-markram synapse model, and this is largely what I'll be working on today and next week.

This week has felt like a bit of a tough wall climb, which is fitting because today my manager is attempting his most intense alpine excursion to date.

At the beginning of the week I started to try to create a block version of the classic STREAM test to measure bandwith between DRAM and the CPU. The basic recipe was worked out with a few kinks on the first day, but I began to compare compression vs non-compression bandwith measurements, and soon felt pretty uncertain about what I had been working on: seems like no matter what I did the non-compression runs would far outperform the compressed ones (see this ggplot for informal demonstration compression vs non-compression bandwith measurements).

comp vs non-comp bandwith

For some reason the rest of the week I was consumed with trying to amend this, but on thursday I had a skype call with my manager, and his response was "yes that's what we expect, and its not likely to change."

I'm torn between being happy that this isn't an indication of something seriously wrong with the project, but it is also a demonstration of my misunderstanding of why we are running compression in memory if not for speed gains.

Anyways, today and next week I'll be converting the STREAM benchmark operations to a parallelized version, and then applying that process to the Tsodyks-Markram neuron model that Francesco has given me some information on.

This week started with needing to resolve a lingering issue where the open mp version of my stream benchmark was prone to having a host of memory error (seg faults, double free's, corruption of several varieties). I had spent the rest of last friday trying to figure this out, but had yet to track down the problems. When I decided to handle something a little more tractable like why the simple = assignment wasn't allowed for storing our blocks in an array I stumbled upon a two birds one stone situation: the resolution of the assignment issue closed up the larger issue with its multitude of frightening messages. This meant that I am now able to create realistic methods of the actual bandwiths that my computer is capable of where the block is concerned.

On wednesday I spoke with my mentor about going back to work more on the tsodyks-markram model for synaptic weight adjustment. He told me that the basic way that I had designed it left out calculations that were supposed to be happening on a synapse basis. We will just be leaving that for a little while, but hopefully for not too long because that seemed interesting.

At this point we are now going forward with a means of measuring how the complexity of computation will change whether the compression makes a meaningful difference in the overall run time. I started to draft a measurement program that will start with very simple computations, move up to using differential equations that have known solutions, and get as complicated as performing a Euler method for solving a differential equation. Ideally by the final category of computation we will see that compression methods contribute negligible amounts to the total time.

That's where I'm at these days! Cheers

week12

week13

I'm forgetting what weeks we went up to, but this small post should serve to tie up all the events that occurred since the previous installment. I completed the workshop, and managed to put together a really brief demonstration on adding interfaces to the Nipype imaging workflow tool. The next big hurdle was presenting my summer's work at the INCF congress. I had a few very short nights leading up to this, but assembled a somewhat comprehensive presentation of in memory compression tools for Neuroinformatics applications. The rest of the congress was very eye opening as to what work is going on in the Neuroinformatics world, and by the end of it I was pretty wiped out.

The time that I had left in the city went into finishing the report. As tricky at times as it was to describe the summer in a sufficiently detailed manner I think it has helped clarify why DRAM can present a bottleneck, and what the relationship is between various types of memory(virtual vs RAM), caches, and the central processor. No doubt there is much more for me to learn and discover, but at the end of this summer of code, I feel like I have learned an inordinate amount from this project, and helped to meet a few of our original goals investigating in memory compression for Neuroinformatics applications.

Tomorrow I fly to Geneva, and actually get to meet the folks I've been working with since the start of the Summer!

Thanks for reading, and stay posted for other projects to come.